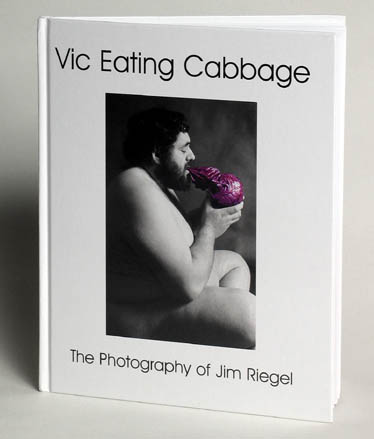

“I became

interested in photographing the nude around 1973. I was annoyed that most

photographs of the nude dealt with the body as fantasy sexual object,

or as sanitized light and form devoid of personality. I wanted to see

if I could portray the nude as real people in a non-sexual and matter-of-fact

way.”

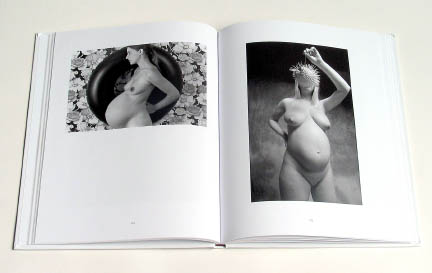

“My first nude portraits were of friends and acquaintances who wanted

to see what it would be like to model nude in a non-threatening environment.

As I became more comfortable working with the nude portrait I began to

add props and situations to the photo session. I still work with the general

theme of being naked in front of the camera, but from there I try to evoke

a multi-layered mood or emotion, be it serious, humorous, satirical, sensual,

disturbing or a combination of the above.”

Jim Riegel

1. Bodies

There are good photographers around who make individual photographs of

equal interest and importance to those produced by Jim Riegel. But in

the case of most of them there is no overall objective in their work,

other than the desire to produce an interesting composition, and to win

the applause of their audience. In the end this is all their work amounts

to; a whole heap of desire for applause.

The essential difference with Jim's photography is that there is a leading

idea informing the whole body of his work, and, by using a systematic

approach tied to this leading idea, each image adds something to the whole,

and each image, seen in the context of the whole, says something more

than it would on its own.

It was something of a revelation to me that there was actually somebody

out there photographing the nude as a human being. Had it been done before?

Absurd as it seems, I couldn't remember having seen the approach used

consistently. As Jim says in the opening statement above, nude photography

was mainly either fantasy sex or just light hitting forms, and with both

approaches there seemed to be an almost obsessive (and rather silly) attempt

to deny that what was being photographed was actually a human being with

personality.

I made some prints of Jim's photographs, and showed them to a few people

to see what sort of reaction I would get. A whole ocean of issues came

up. There were people who were positively turned off by any representation

of the naked human body. There were others who thought that the only bodies

they wanted to see represented were so called 'beautiful people', ie bodies

which conformed to the tight stereotype of what our culture (or perhaps

media) says a body should look like. There were those who thought that

it was OK to show some bits of the body but not other bits. And there

were those who just wanted to mock the people in the photographs.

From these reactions, I realised that in the process of looking at Jim's

photographs, we are led to confront not only the question of how we respond

to issues of nudity and sexual provocation, but, because he is showing

us nudes as people, we are also drawn into looking at the issue of how

we relate to our own bodies. There is no doubt that this can get uncomfortable.

The issues of sexual response and how we relate to our own bodies are

connected of course. But the body issue is a wider and broader thing,

and is established very early on in our lives, certainly before we have

any sort of conscious control over what is happening to us. For this reason,

it becomes difficult to discuss rationally. I realised that with some

people I was dealing with a whole host of basic fears and uncertainties

which had probably been with them since early infancy, and which were

using the rational part of that person’s brain to protect themselves.

Tacked onto these fundamental issues related to how we live in our bodies,

there are, of course, a whole host of neuroses about weight, body hair,

shape of nose, disposition of eyes, regularity of feature, youth and so

on, which become part of our consciousness as our personality develops

through seeing and feeling how other people react to us. These neuroses

get constant reinforcement from the media who, despite the competitive

nature of the industry, are united in pushing one agenda: the idea that

to look good is to be good. Appearance is essence. To look good is to

feel good and to have value as an individual. If it were not the case,

what would be the point of buying any of the thousands of products which

are targeted at changing the appearance, enhancing status, making the

buyer look cool or sophisticated, elegant or fashionable, strong or desirable?

Jim's photography addresses these issues directly by presenting us with

examples of human beings who are not paradigms of youthful desirability.

Many of the embarrassed reactions I got to the images I showed around

just spoke of the viewer's own problems with being overweight, underweight,

undersized, oversized, too hairy, too dark, too spotty, too freckled…you

name it, somebody's got too much of it, or too little, and they are made

to feel bad about it. We are picked on for what is different about our

bodies. Deformed or handicapped people have it even worse. Viewed rationally,

the whole thing appears manifestly absurd. You are what you look like.

Everybody knows it's untrue. 2. Aesthetics.

To many people, aesthetics is something far removed from ordinary life.

It's what happens in museums, art galleries and concert halls and is the

prerogative of the rich, who wear it like a badge of superiority. Unfortunate,

because in reality aesthetics (from Greek : perception) goes to the very

roots of everyday experience.

I was at the Bowes Museum in County Durham a few years ago. In the entrance

hall stands a large silver swan in a glass case, the wings of which open

on the hour, every hour, then close again. The museum itself is overloaded

with giant oil paintings in heavy gilt frames depicting handsome men in

wigs showing off their badges of status, winsome maidens, historical scenes

of appropriate gravitas, idealised classical landscapes and so on. It

was all very fine. I wandered around the exhibits until I came across

a small almost monochrome oil painting by Goya. Maybe the effect was heightened

because of the context, I don't know, but that little black and white

painting travelled the distance between Spain and England, between the

19th and 20th centuries in an instant, eclipsing all of the fancy paraphernalia

around it. It was human experience presented starkly and accurately from

the pen of a human being intent on recording what was going on around

him. It recorded what was, a moment, a situation. It was not beautiful,

except in the sense of its power to convey, its power to record, its power

to move, the power of the truth. It's the type of experience that makes

your primitive particles dance. And, at its best, that's essentially what

the business of art is, a beautiful accord between means and expression,

an accord which comes across as a uniquely powerful experience, connecting

us immediately and strongly with the artist who made it. No matter what

the time and distance, we feel his knowledge, his intelligence, his humanity,

his perception.

Harmonious proportions, creativity, inventiveness, the investigation and

recording of issues of fundamental importance to human beings, pattern,

repetition, echoes, clues to the eternal, the application of intelligence

and imagination to problems, riddles, paradoxes and processes, using different

media, producing observations on and embellishments to the society in

which we live: these have all been the pre-occupations of artists through

the centuries. And this is the tradition continued by Jim Riegel. It’s

a tradition which engages not only the artist, but also the scientist

and the philosopher, a tradition which is rooted in curiosity about the

world and how it works, and which seeks to express the harmonies and dissonances

of the world in material form.

There are, of course, plenty of other agendas for art: it has been equated

with fashion, with self expression, in fact with any set of qualities

that can be put together and sold at a high price. This is an impoverishment

of both art and the language. There are plenty of words for these other

activities : advertising, marketing, fashion and elitist self indulgence

are a few that spring to mind. They all lay claim to the word ‘art’

simply because it is financially and socially advantageous to do so. If

there were neither money nor status to be had, they would quickly leave

it alone.

Jim’s art is not concerned with these externals. In defining his

objective as that of showing the nude with personality, he is targeting

his interest on the relationship between what someone appears to be (their

physical form, their nudity) and what they are (their personality, their

inner self). Taking away the clothes is a masterstroke, because the individual

no longer has the badges of identity to hide behind. It makes it much

more likely that the real person will appear sometime during the photo

session. And it opens up subject matter which is of profound interest

to human beings, and also for which the camera is well suited as a means

of exploration.

It’s important to note that there is no sordid striving after sensationalism

by depicting the deformed or obscene in Jim’s photography. Such

an approach does not address anything deeper than pornographic or fashion

photography, both of which rely on our response to the human being as

an object.

In this he is fundamentally different to some ninety five percent of photographers

who latch onto the external aspects of their subject matter in the belief

that this is all a photograph can show. Sex, or light hitting form. For

both approaches, there is nothing but the body as an object: an object

of desire, or an object being hit by light. At bottom, it’s not

very interesting. Its popularity is driven by the appetites, and the whole

narcissistic obsession with desire and gratification, its appeal transient

and often based on novelty, its value temporary, though sometimes resurrected

as nostalgia, another desire close to self love, love of my past and those

cultural artefacts that connect me to it. In short love of me, albeit

a past me.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with sex and light hitting form per

se. But the approach does represent something qualitatively different,

and it does seem important to make distinctions between what is happening

based on these different approaches. Making distinctions in this way is

a process which enriches our perception (aesthetic). The Eskimoes have

49 (or so) different words for ice. In the arctic tundra they see a world

rich in diversity, of which we are unaware. The same applies to the world

of cultural artefacts. There is a similar richness and variety for those

who can see. In this richness, and the profound resonances which accompany

it, lies the essential benefit of pursuing aesthetics (perception). It

requires working at, because it is nearly always based on background knowledge.

It is valuable not only as a thing in itself, but also as a means of communication,

because there is here a common heritage which expresses and preserves

common ideas, aspirations and spirituality.

Civilisation, humanity itself is very close to its expression in cultural

artefacts. The North Vietnamese civilian, reduced to living in underground

tunnels for days on end by napalm bombing, retained a sense of identity

and humanity through his songs, ie through his own cultural and aesthetic

heritage.

John Lao

|